PatriciaFeinman.com

There was a maple-tree-lined path leading from our backyard to the lake in the park at the bottom of our land. Every winter, local people would tap our trees for syrup. They’d been doing it for generations and weren’t about to ask us for permission. Ditto the kids on three-wheelers who used to fly down the path and across our lawn. One day they startled themselves (and Art and me) because Art was sunbathing naked, right in their trajectory.

Read the rest at https://www.litromagazine.com/usa/2023/12/living-where/

Art and I smoked in every nook and cranny of our house. The walls were orange-streaked with nicotine, the carpets and upholstery permeated with the odor of stale tobacco and smoke. We were resentful when non-smoking guests and family members came to visit, because it meant we couldn’t smoke in our own home. We smoked in the car, we smoked in the back room of our shop—no doubt chasing customers away. The air was thick with it. Our hair and every piece of clothing we owned were impregnated with the stench of smoke—we stank of smoke—but we didn’t care, because we loved smoking.

Read the rest at https://maydaymagazine.com/smoking-with-art-by-patricia-

feinman/

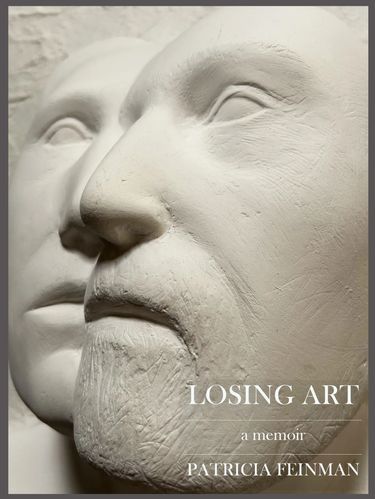

I got as close to Art as I could, resting one arm on either side of him, without letting any of my weight lean on his emaciated body. I looked into his face. It’s okay, my love, I said. You can go … I’ll be okay. It was a lie. I had no idea if I would survive the loss of him.

Careful to avoid any of the tubes that were attached to him, I lay next to him. Art’s grown daughter Zoë—our daughter now in every way that mattered—crawled onto our marriage bed and positioned herself on his other side. I’ll be okay Dad, she said. You can go.

Read the rest at https://minervarising.com/losing-art-an-excerpt-from-losing-art-a-memoir-by-patricia-feinman/

Art and I sat in Big Blue Truck in the rain in front of our Main Street shop, with the windshield wipers going steadily back and forth, watching people scoot by.

It had been Art’s idea—born of both fear and desperation—to expand our tile manufacturing business to include retail, after it became clear that the revenue from tile-making was not going to be enough. We were an artist and a writer, neither one of us had any experience at all in manufacturing or retail, not to mention dealing with the second and third generation welfare recipients who made up the workforce in this small, depressed upstate New York town. We had just moved here from East Hampton in an attempt to save our floundering business—and we were completely out of our league—constantly on the verge of losing what little we had.

Read the rest at https://www.whlreview.com/no-17.1/essay/PatriciaFeinman.pdf

Smoking With Art, Mayday Magazine, Spring 2022

The Stick-Up Artist, Wilderness House Literary Review, Spring 2022

The Ninth Circle of Catskill, The Dillydoun Review, Spring 2022

Losing Art (an excerpt), Minerva Rising, Spring, 2022

Ghost of Valentine’s Day Past, New Mexico Review, Fall, 2022

Are We Still Soulmates? North Dakota Quarterly, Fall/Winter 2022

Living Where? Litro Magazine, Fall, 2023

We use cookies to analyze website traffic and optimize your website experience. By accepting our use of cookies, your data will be aggregated with all other user data.